Whole Genome Shotgun Sequencing

Before we begin, some thought experiments:

Thought experiment: How big are genomes of phages, Bacteria, Archaea, Eukarya?1

Thought experiment: Suppose that you want to sequence the genome of a bacteria that is 1,000,000 bp and you are using a sequencing technology that reads 1,000 bp at a time. What is the least number of reads you could use to sequence that genome?2

Thought experiment: The human genome was “finished” in 2000 — to put that in perspective President Bill Clinton and Prime Minister Tony Blair made the announcement! — How many gaps remain in the human genome?3

A long time ago, when sequencing was expensive, these questions kept people awake. For example, Lander and Waterman published a paper describing the number of clones that need to be mapped (sequenced) to achieve representative coverage of the genome. Part of this theoretical paper is to discuss how many clones would be needed to cover the whole genome. In those days, the clones were broken down into smaller fragments, and so on and so on, and then the fewest possible fragments sequenced. Because the order of those clones was known (from genetics and restriction mapping), it was easy to put them back together.

In 1995, a breakthrough paper was published in Science which the whole genome was just randomly sheared, lots and lots of fragments sequenced, and then big (or big for the time — your cell phone is probably computationally more powerful!) computers used to assemble the genome.

This breakthrough really unleashed the genomics era, and opened the door for genome sequencing including the data that we are going to discuss here!

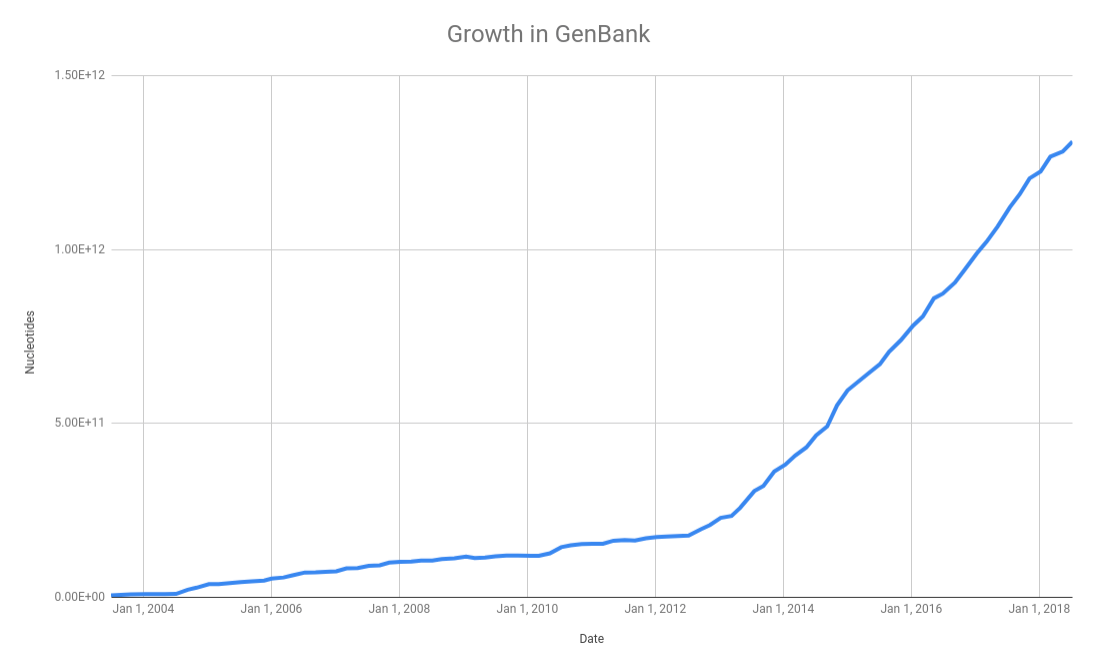

As we discussed in the databases class, the NCBI GenBank database is a central repository for all the microbial genomes. In their release notes they summarize the growth in the number of bases over the last few years:

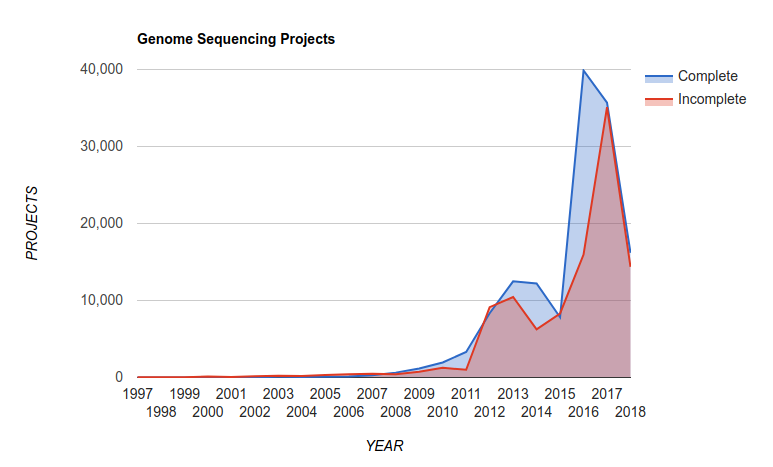

and this translates into a growth in the number of complete microbial genomes released over the last few years as reported in the Genomes Online Database:

There are now over 300,000 complete genomes in the GOLD database! Read the last version of their paper Genomes OnLine Database (GOLD) v.6: data updates and feature enhancements Nucl. Acids Res. (2016); doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw992

Also, at the time of writing this (September, 2018), PATRIC reported 177,395 bacterial genomes in their database.

Thought experiment: Back in the 1990s, we had a few tens of genomes. In the late-1990s we were betting on whether we would reach 100 complete genomes. What happened? Why do we now have hundreds of thousands of genomes?4

How do we sequence a genome?

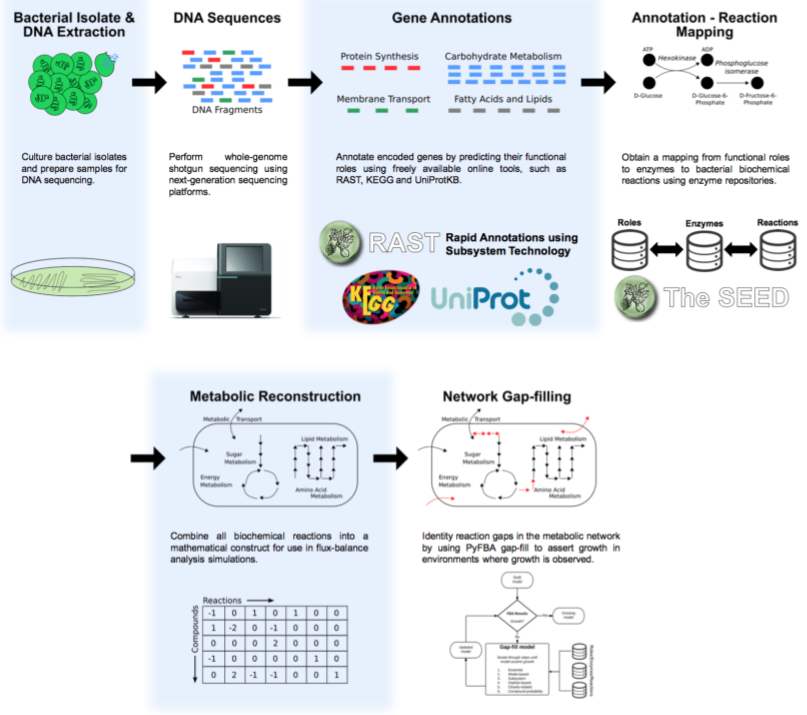

The basic process to sequence the genome is shown in this figure:

We start with purified DNA and shear it and make a library using either the Covaris ultrasonicator or the Illumina Nextera tagmentation protocol as described in the Sequencing chapter under making the libraries.

Once the sequences come back from the sequencer, they are in fastq format, and the first thing to do is some Quality Control and Quality Assurance. Following that, we need to assemble the short fragments of reads, that are typically just a couple of hundred base pairs long into fragments that are kilobases or megabases long.

Assembly of short DNA sequences is conceptually an easy problem:

If the 5′ end of one sequence is the same as the 3′ end of another sequence the data is said to overlap. If the overlap is of sufficient length to distinguish it from being a repeat in the sequence the two sequences must be contiguous. The data from the two sequences can then be joined to form one longer continuous sequence.

This is an adaptation of a quote in this 1979 paper by Roger Staden that I first read from this 2017 paper by Adam Phillippy.

But in reality it is an NP-hard problem, especially given the numerous repeats and complexities of genomes. Biology likes to make things complex! In fact, it is the phrase distinguish it from being a repeat in the sequence that is the most difficult part about genome assembly!

On your AWS images we have provided:

Some other assemblers you might consider include:

I personally prefer Spades, but everyone has their own favorite assembler!

Though experiment: How much sequencing do you need for a bacterial genome?5

Obviously the more sequencing you have — we call it sequencing depth or sequencing coverage — the more likely you are to complete the genome. If you only have a small portion of the genome (e.g. 10%) you are going to be unable to complete the genome into a single contiguous sequence — a single contig. In contrast, if you have sequenced every base in the genome multiple times, and the reads start at random places, you should be able to assemble the whole genome into one, or a few, contigs.

Remember, there is also a list of definitions you can refer to!

The next step in annotating a genome, after the short reads have been assembled into sequences, is to identify the open-reading frames.

Once you have identified those open reading frames, we need to assign functions to them — what is it that the proteins that are encoded by those open reading frames are doing in the cell?

There are several different ways of doing this, but many of them rely on measuring sequence similarity. As we progress through the course we will discuss ways of measuring that.

Thought experiment: If I find the identical protein sequence in two different organisms, is it doing the same function in both organisms?

1 Answer: on average, phages are 50kb, Bacteria and Archaea are 2 Mb, and Eukarya are 2GB

2 Answer: Of course, if you knew exactly the order of the reads, you could sequence 1,000 reads and sequence the whole genome.

3 Answer: According to this 2017 paper there are approximately 800 gaps remaining in the human genome!

4 Answer: First, the cost of sequencing dropped drastically, and second, we realized the amazing amount of information we can get from hundreds of genomes.

5 Answer: The average bacterial genome is about 2,000,000 bp, and for good assembly with Illumina data you need about 100x coverage, so you need about 0.2 Gbp (200,000,000 bp) of sequence data. Therefore, you can sequence a lot of genomes on a HiSeq! However, assembly is much better with long read systems like the Minion or PacBio.